Martin Luther King Jr. Day

1929—1968, American clergyman and civil rights leader

Biography of Martin Luther King Jr.

Born in Atlanta, Georgia, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., graduated from Morehouse College (B.A., 1948), Crozer Theological Seminary (B.D., 1951), and Boston University (Ph.D., 1955). The son of the pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, King was ordained in 1947 and became (1954) minister of a Baptist church in Montgomery, Ala. He led the black boycott (1955—56) of segregated city bus lines and in 1956 gained a major victory and prestige as a civil-rights leader when Montgomery buses began to operate on a desegregated basis.

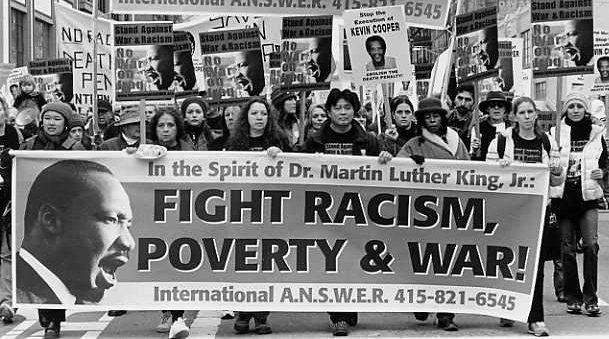

King organized the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which gave him a base to pursue further civil-rights activities, first in the South and later nationwide. His philosophy of nonviolent resistance led to his arrest on numerous occasions in the 1950s and 60s. His campaigns had mixed success, but the protest he led in Birmingham, Ala., in 1963 brought him worldwide attention. He spearheaded the Aug., 1963, March on Washington, which brought together more than 200,000 people. In 1964 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

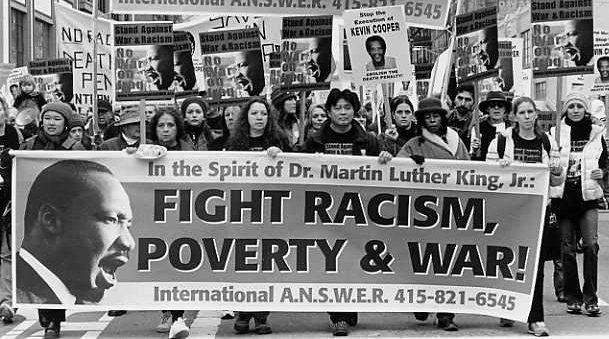

King's leadership in the civil-rights movement was challenged in the mid-1960s as others grew more militant. His interests, however, widened from civil rights to include criticism of the Vietnam War and a deeper concern over poverty. His plans for a Poor People's March to Washington were interrupted (1968) for a trip to Memphis, Tenn., in support of striking sanitation workers. On Apr. 4, 1968, he was shot and killed as he stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel (since 1991 a civil-rights museum).

James Earl Ray, a career criminal, pleaded guilty to the murder and was convicted, but he soon recanted, claiming he was duped into his plea. Ray's conviction was subsequently upheld, but he eventually received support from members of King's family, who believed King to have been the victim of a conspiracy. Ray died in prison in 1998. In a jury trial in Memphis in 1999 the King family won a wrongful-death judgment against Loyd Jowers, who claimed (1993) that he had arranged the killing for a Mafia figure. Many experts, however, were unconvinced by the verdict, and in 2000, after an 18-month investigation, the Justice Dept. discredited Jowers and concluded that there was no evidence of an assassination plot.

King wrote Stride toward Freedom (1958), Why We Can't Wait (1964), and Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (1967). His birthday is a national holiday, celebrated on the third Monday in January. King's wife, Coretta Scott King, has carried on various aspects of his work. She also wrote My Life with Martin Luther King (1989).

The History of Martin Luther King Day

It took 15 years to create the federal Martin Luther King, Jr., holiday. Congressman John Conyers, Democrat from Michigan, first introduced legislation for a commemorative holiday four days after King was assassinated in 1968. After the bill became stalled, petitions endorsing the holiday containing six million names were submitted to Congress.

Conyers and Rep. Shirley Chisholm, Democrat of New York, resubmitted King holiday legislation each subsequent legislative session. Public pressure for the holiday mounted during the 1982 and 1983 civil rights marches in Washington.

Congress passed the holiday legislation in 1983, which was then signed into law by President Ronald Reagan. A compromise moving the holiday from Jan. 15, King's birthday, which was considered too close to Christmas and New Year's, to the third Monday in January helped overcome opposition to the law.

National Consensus on the Holiday

A number of states resisted celebrating the holiday. Some opponents said King did not deserve his own holiday contending that the entire civil rights movement rather than one individual, however instrumental, should be honored. Several southern states include celebrations for various Confederate generals on that day. Arizona voters approved the holiday in 1992 after a threatened tourist boycott. In 1999, New Hampshire changed the name of Civil Rights Day to Martin Luther King, Jr., Day.

March on Washington (August 28, 1963)

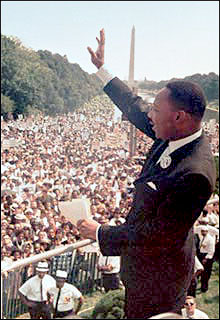

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom took place in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. Attended by some 250,000 people, it was the largest demonstration ever seen in the nation's capital, and one of the first to have extensive television coverage.

Background

1963 was noted for racial unrest and civil rights demonstrations. Nationwide outrage was sparked by media coverage of police actions in Birmingham, Alabama, where attack dogs and fire hoses were turned against protestors, many of whom were in their early teens or younger. Martin Luther King, Jr., was arrested and jailed during these protests, writing his famous "Letter From Birmingham City Jail," which advocates civil disobedience against unjust laws. Dozens of additional demonstrations took place across the country, from California to New York, culminating in the March on Washington. President Kennedy backed a Civil Rights Act, which was stalled in Congress by the summer.

Coalition

The March on Washington represented a coalition of several civil rights organizations, all of which generally had different approaches and different agendas. The "Big Six" organizers were James Farmer, of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE); Martin Luther King, Jr., of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); John Lewis, of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC); A. Philip Randolph, of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; Roy Wilkins, of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); and Whitney Young, Jr., of the National Urban League.

The stated demands of the march were the passage of meaningful civil rights legislation; the elimination of racial segregation in public schools; protection for demonstrators against police brutality; a major public-works program to provide jobs; the passage of a law prohibiting racial discrimination in public and private hiring; a $2 an hour minimum wage; and self-government for the District of Columbia, which had a black majority.

Opposition

President Kennedy originally discouraged the march, for fear that it might make the legislature vote against civil rights laws in reaction to a perceived threat. Once it became clear that the march would go on, however, he supported it.

While various labor unions supported the march, the AFL-CIO remained neutral.

Outright opposition came from two sides. White supremacist groups, including the Ku Klux Klan, were obviously not in favor of any event supporting racial equality. On the other hand, the march was also condemned by some civil rights activists who felt it presented an inaccurate, sanitized pageant of racial harmony; Malcolm X called it the "Farce on Washington," and members of the Nation of Islam who attended the march faced a temporary suspension.

The March on Washington

Nobody was sure how many people would turn up for the demonstration in Washington, D.C. Some travelling from the South were harrassed and threatened. But on August 28, 1963, an estimated quarter of a million people about a quarter of whom were white marched from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial, in what turned out to be both a protest and a communal celebration. The heavy police presence turned out to be unnecessary, as the march was noted for its civility and peacefulness. The march was extensively covered by the media, with live international television coverage.

The event included musical performances by Marian Anderson; Joan Baez; Bob Dylan; Mahalia Jackson; Peter, Paul, and Mary; and Josh White. Charlton Heston representing a contingent of artists, including Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando, Diahann Carroll, Ossie Davis, Sammy Davis Jr., Lena Horne, Paul Newman, and Sidney Poitier read a speech by James Baldwin.

The speakers included all of the "Big Six" civil-rights leaders (James Farmer, who was imprisoned in Louisiana at the time, had his speech read by Floyd McKissick); Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish religious leaders; and labor leader Walter Reuther. The one female speaker was Josephine Baker, who introduced several "Negro Women Fighters for Freedom," including Rosa Parks.

Noteworthy Speeches

The two most noteworthy speeches came from John Lewis and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Lewis represented the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a younger, more radical group than King's. The speech he planned to give, circulated beforehand, was objected to by other participants; it called Kennedy's civil rights bill "too little, too late," asked "which side is the federal government on?" and declared that they would march "through the Heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did" and "burn Jim Crow to the ground–nonviolently." In the end, he agreed to tone down the more inflammatory portions of his speech, but even the revised version was the most controversial of the day, stating:

"The revolution is at hand, and we must free ourselves of the chains of political and economic slavery. The nonviolent revolution is saying, 'We will not wait for the courts to act, for we have been waiting hundreds of years. We will not wait for the President, nor the Justice Department, nor Congress, but we will take matters into our own hands, and create a great source of power, outside of any national structure that could and would assure us victory.' For those who have said, 'Be patient and wait!' we must say, 'Patience is a dirty and nasty word.' We cannot be patient, we do not want to be free gradually, we want our freedom, and we want it now. We cannot depend on any political party, for the Democrats and the Republicans have betrayed the basic principles of the Declaration of Independence."

King's speech remains one of the most famous speeches in American history. He started with prepared remarks, saying he was there to "cash a check" for "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness," while warning fellow protesters not to "allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force." But then he departed from his script, shifting into the "I have a dream" theme he'd used on prior occasions, drawing on both "the American dream" and religious themes, speaking of an America where his children "will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character." He followed this with an exhortation to "let freedom ring" across the nation, and concluded with:

"And when this happens, when we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, 'Free at last, free at last. Thank God Almighty, we are free at last.'"

Excerpt from Martin Luther King's "I Have a Dream" Speech

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered this speech on August 28, 1963, on the steps of the Washington, D.C., Lincoln Memorial during the march on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. For the full text, see the Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers project at Stanford University, www.stanford.edu/group/king.

"I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.” I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slaveowners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a desert state, sweltering with the heat of injustice and oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today."